Definition of DSL

A DSL is a computer language, specialized for a specific domain. A DSL is essentially the opposite of a general programming languages(GPL), I mean every language that can be used to develop something. For example, Java, C#, and Scala are all GPL languages. With a DSL, we want only to solve a specific domain problem, so we design the language specifically for the domain. A DSL can’t be used outside of the domain, because it is not designed for flexibility.

Scala provides a unique combination of language mechanisms that make it easy to write your own custom DSL. In general, writing DSLs categorized in two major group:

- Internal DSL

- External DSL

Difference Between Internal and External DSLs

An internal, or embedded DSL is one that is created internally in a GPL, for example, when we create a set of classes with Java to solve a domain problem. Internal DSLs are very useful for creating an application program interface (API). When we use an embedded DSL, we are using a subset of the GPL to create our language, and, therefore, we lose all the flexibility associated with the GPL. On the other hand, however, we can build software that is more readable by the domain expert. This means that the developer can solve an issue or change a functionality faster. For example, if we want to parse an Excel file, we can have a code like the following:

LoadFile("C:\file.xls")

.read_column("A1")

.read_column("A2")

.save_CSV("file.csv")

An external DSL is a kind of DSL that is not correlated with a language. CSS or a regular expression are good examples of external DSLs.

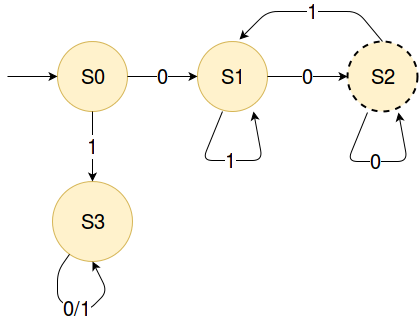

In this tutorial, I ‘m going to write internal DSL for representing Deterministic Finite Automaton. It ‘s basically a finite-state machine that accepts some input and tells us whether it has accepted the input or not. It consumes input from start to end, and at each step it changes it’s internal state. Input will be accepted if the DFA’s position is on one of the final states. For example blow is the DFA that accepts all input that starts and ends with 0:

If you haven’t heard DFA before I highly recommend to read the formal definition of DFA before continue. At the end of this article we will build a DSL like this:

val dfa = newDfa { dfa =>

dfa states {

Seq(S0, S1, S2, S3)

}

dfa finalStates {

Seq(S2)

}

dfa transitions { transition =>

transition on '0' from S0 to S1

transition on '1' from S0 to S3

transition on '0' from S1 to S2

transition on '1' from S1 to S1

transition on '0' from S2 to S2

transition on '1' from S2 to S1

transition on '0' from S3 to S3

transition on '1' from S3 to S3

}

} startFrom S0 withInput "010101011110110110000"

val hasInputAccepted = dfa.run

This code is exactly correspondens to the picture above, representing DFA that accepts all input that starts and ends with zero. Ok, let’s start coding.

At first line you see something like this:

newDfa {

// code removed for brevity

}

It ‘s not a function definition! Exactly opposite, it ‘s a function call. In scala we can replace parameter parentheses with curly braces. If you have a function like this:

def add2(n : Int) = n + 2

You can call it like this:

add2 {

println("Hello world!")

5 * 4

}

It prints Hello world! to the console and the result of the function is 22. The other aspect of the code is that we ‘ve called newDfa like a function. Of course it is a method because we want modularity and encapsulation. It ‘s defined in Dfa companion object and we have imported it:

class Dfa {

// code removed for brevity

}

object Dfa {

def newDfa(...){

// code removed for brevity

}

}

import Dfa._

Next, we look inside the newDfa method call:

dfa states {

Seq(S0 , S1 , S2 , S3)

}

dfa finalStates {

Seq(S2)

}

dfa transitions { transition =>

transition on 'A' from St0 to St2

transition on 'B' from St0 to St1

}

newDfa accepts a function of Dfa => Unit. newDfa is an example of a higher-order function. Higher order functions take other functions as parameters or return a function as a result. You can configure your automata inside this method. For example you can define all the states via:

dfa states {

Seq(S0 , S1 , S2 , S3)

}

states is one of the Dfa’s methods. In scala you can replace dot with space for invoking methods that take one argument. So above code could be written as:

dfa.states {

Seq(S0 , S1 , S2 , S3)

}

or

dfa.states(Seq( S0 , S1 , S2 , S3))

But the former is more readable. I also modeled DFA’s states like this:

sealed trait State

final case object S0 extends State

final case object S1 extends State

final case object S2 extends State

final case object S3 extends State

Of course you could model states as simple string like “S0” or “S1” but this way is more type safe. finalStates method is also like states method so let’s jump to the transitions method. The interesting thing, is in transitions block:

transition on 'A' from St0 to St2

transition on 'B' from St0 to St1

It ‘s just infix notaion method call mixed with some method chaining. transition is a parameter of type Transition which has 3 methods: on, from, to:

class Transition {

// code removed for brevity

def on(ch: Char) : Transition = ???

def from(s: State) : Transition = ???

def to(s: State) : Transition = ???

}

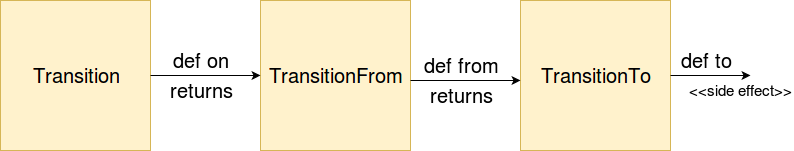

But defining Transition type like this has one drawback and that is ordering. User can call any of these methods in any order that he wants but I didn’t like that so I refactored Transition into 3 class that each class has exatcly one method, each method returns the other class in the chain. The picture below depicts the idea:

Another way to enforce method ordering

Another way to enforce method ordering is through phantom types, types that never get instantiated. Understanding these ghosts :) requires another full article. So I urge you to read this awsome article about phantom types https://blog.codecentric.de/en/2016/02/phantom-types-scala/ and implement method chaining with phantom types as a exercise.

conclusion

In nutshell, when you write DSL in scala, higher-order functions, curly braces, infix notaion and method chaining(fluent interfaces) will comes handy. If you want to go deeper, I recommond reading Apress Practical Scala DSLs. You can find the full source code here.